This week’s article is focused less on macro. Instead, I’m sharing observations from a recent trip through some of China’s textile factories in Guangdong province and the shortcomings of top-down industrial policy. But here are some quick notes on recent events worth keeping in mind:

China’s state banks lowered rates on deposits last week in an attempt to encourage savers to move out of timed deposits. Then on Monday the PBoC cut its seven-day reverse repurchase rate by 10 basis points from 2% to 1.9%. My instinct is these measures alone can’t meaningfully improve consumption figures, but they show the government is aware of the challenges facing the economic recovery. There’s talk of more easing measures to come.

A recent scoop from the Sing Tao Daily reported that China’s ambassador to France, Lu Shaye, is being recalled to Beijing after his comments about post-Soviet countries’ sovereignty (link is to the English sister paper The Standard). This hasn’t been picked up by Western outlets yet, so I assume they are still confirming it, but if true is another promising sign that Beijing is moderating its tone with foreign counterparts.

The Biden Administration extended exemptions for Taiwanese and South Korean chipmakers to continue operations in China. This is encouraging from a rapprochement point of view.

Also, the US is handling the Cuba situation delicately — apparently in an attempt to keep dialogue going. This is a rare instance where a White House Spokesperson tying themselves up in knots makes some sense.

Whether diplomacy can reverse the deepening “China discount” in markets depends on how substantive any rapprochement is. Secretary of State Blinken’s upcoming trip to Beijing is likely part of the feeling-out process, and President Xi’s planned trip to San Francisco in November for the APEC conference could be the culmination of a timeline for a symbolic reset.

The US has about six months before it enters election season and relations with China take a backseat to political theatrics. I expect most presidential candidates to take vocal anti-China stances, so maybe any upcoming diplomatic efforts won’t make a difference for skittish foreign investors.

Now, onto China’s textile industry.

“Swallowed up in one phase or other of its immensity, towards which they seemed impelled by a desperate fascination, they never returned.”

— Charles Dickens on people’s mysterious attraction to London (from Dombey and Son)

China is responsible for about 40% of the world’s textile exports, making it the world’s largest producer of clothing. If Guangzhou is a hub for China’s clothing industry, the Zhongda textile market lies at its knotty core. Starting in the 1980s, fabric merchants began congregating in this part of the city, which is just a couple kilometres from downtown in Haizhu district. Technically it is a series of villages such as “Kangle” and “Lujiang”, but it is a continuous area filled with winding streets, buildings bulging with workshops, and roads clogged with motorbikes ferrying bolts of cloth to and fro between small businesses. Off the main thoroughfares are “handshake buildings” — named thus because neighbours in opposite buildings can shake hands.

A handshake building and a crumpled government banner telling renters to register with local authorities:

Source: William Sandlund

Next to Zhongda is the orderly “China Fabrics and Accessories Centre,” essentially a permanent exhibition hall for factories from around the country to market their services. The building is 7 stories high, and has roads on the ground floor to help move massive bolts of fabric and product to the stalls. This is just one of many enormous exhibition centres in the district. A friend doing sourcing for a Pakistan-based clothing brand brought me to the centre. He was searching for a lace manufacturer to make a small batch of clothes to be sold through Instagram to customers in places like Karachi, Lahore, and Faisalabad. He and his managers were impressed with the quality, variety, and price of lace — a sign of China’s enduring strength in textile manufacturing, despite some headlines to the contrary.

Source: William Sandlund

In the basement are some workstations, but you need to leave the building and enter the sprawling village area to see the workshops and small factories where you can get a new line of clothes designed and produced in 24hrs. Companies like Shein collaborate with workshops to quickly churn out designs they can test on the market — successful lines can then be scaled up at larger factories in more distant areas for fast-fashion hungry Gen-Z consumers in the west.

A small workshop in Zhongda versus a larger factory in far-flung part of Guangdong:

Source: William Sandlund

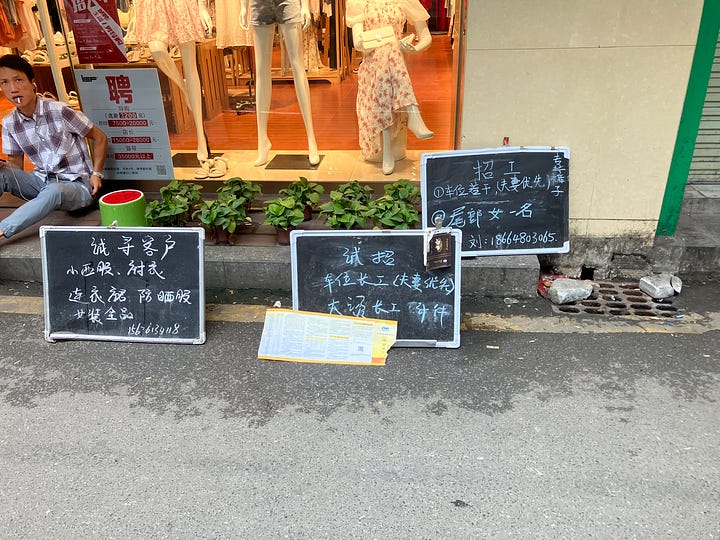

Zhongda is the closest approximation to the Victorian London described by Charles Dickens I have encountered. There is work, idleness, regular life, buzzing activity, all in an area no bigger than five square kilometres. It is built by the logic of a freewheeling market rather than the steady hand of urban planners. Lining the streets are blackboards scrawled with chalk, “Hiring: Specialist in women’s clothing,” held by agents looking to connect migrant workers with factories. Zhongda is home for just under 500,000 people. Roughly 100,000 of them work in the textile industry. A vibrant service sector supports this core source of employment — warehouses, logistics services, fabric recyclers, dentists, ear-cleaning stalls, restaurants, and grocery stores.

Source: William Sandlund

Is the Zhongda market going to be demolished?

Seen from above, Zhongda is conspicuously low-rise:

Source: William Sandlund, Earth Explorer USGS

This is because it is a “village in the city,” a particularly common phenomenon in southern China. Land use in the country is divided along rural and urban lines — rural land is owned and operated by collectives, while urban land is owned by the municipal government and leased out. Outside of farming, there are strict limitations on how rural land can be used. This means that when a city in China expands into surrounding farmland, the municipal government must first transfer the ownership of the land from the rural collective. In the past, this was a huge source of funding for Chinese cities; prior to relatively recent reforms peasants were compensated based on the values of crop yields, while the municipal authorities auctioned off the land to developers based on market values. In effect, this was a massive transfer of wealth from peasants to local governments and property developers. It’s therefore understandable that some villages like those in Zhongda took matters into their own hands and began to urbanise themselves. This was partly to make a more productive use of land near boomtowns, but also served to preserve their autonomy — it’s much harder for authorities to demolish an urban village than to clear out relatively empty farmland.

But there are rumblings that this is about to happen to Zhongda. In 2019 the government announced it was planning on relocating the Zhongda market to Qingyuan, a sprawling prefectural city 100km north of Guangzhou, allowing the municipality to redevelop the area into a high-tech hub while moving this “low-value industry” to a part of the province with lower costs and more space. News articles from state media (link is in Chinese; use Google Translate to read the article in another language) write that thousands of businesses are already planning to relocate. During Covid the project was put on hold, but earlier this year Caixin published a follow-up article with the headline “Core of Guangzhou’s Textile Industry Is Being Shattered” that claims the plans for the move are being accelerated.

The new Guangzhou-Qingyuan Technology Fashion City:

Source: Nanfang Daily, William Sandlund

The government cites unsafe living conditions, fire hazards, illegal land use, and difficulty taxing the informal economy as reasons they want to redevelop the area. I can sympathise with some of these concerns — the living conditions for many of the migrant labourers who work there do not match their contributions to the local and global economy — but not the solution. Although some would consider the area to be an eyesore, Zhongda is one of the few places in modern urban China that is organic. It is walkable, and feels like a place where the material world of manufacturing collides with humanity in a way that is comprehensible.

When I asked a local if he was worried he laughed and said, “They’ve been saying that for years, but no one here is going to move.”

In order to better understand the situation, I made the journey to the industrial park that will supposedly take over the role of Zhongda market. After mistakenly stumbling onto a different industrial park where a property developer was hawking flats and the courtyard of a brand-new mall housed massive piles of rubble and dirt, I found my way to the “Guangqing technology fashion city.” The day was hot; new industrial parks are shaded by small trees that wilt in the summertime heat. On the drive to the correct park I was surrounded by concrete, construction sites, and the orange clay that lies just beneath the surface of tropical vegetation.

What I found was that the industrial park threatening to displace Zhongda was still largely unfinished. There was an elaborate atrium where you could learn about the project; the exhibit featured many “before” and “after” posters showing how the area was being improved.

But most of the land was empty. And the buildings that were finished did not have activity. Talking to a guide at the site, he told me, “This is a long-term plan. Over three, five years. The government is not going to get rid of Zhongda overnight.”

Source: William Sandlund

There are also private projects in the area banking on the transition of industries from Guangzhou to Qingyuan. Take, for example, the Zhongda Qingyuan project, which is wholly owned by Chung Tai Printing, itself a wholly-owned subsidiary of HKEX-listed Neway Group Holdings (HKEX: 00055). Based on disclosures from Neway Group, the project is a partnership with a local Qingyuan property developer to create an industrial park with “industrial buildings, commercial buildings, apartments and dormitories” in Qingyuan city to lease or sell. But partially due to the strained finances of the local developer, in June of 2022 Neway was looking to sell their stake. While the proceedings are still ongoing, it is just one example of the ways in which distressed property markets in lower tier cities are affecting financing for infrastructure projects like industrial parks. According to Neway’s disclosure at the end 2022, the industrial park was 65% completed but had sold just 15% of the “first stage of development,” hinting at the low demand from the market for such a project.

This is just one example of the weak support for this kind of top-down policy. Beyond the logistics of convincing hundreds of thousands of workers and thousands of businesses to relocate to a government-planned industrial park, I think the scheme belies a deeper problem with how China will achieve economic growth in the coming decades. After all, this programme is essentially part of the infrastructure/investment-driven model of growth where the government subsidises businesses. While this model worked well thirty years ago when much of the country was undeveloped, there is already a profitable and productive area for this particular industry.

As I already mentioned, Guangzhou plans to redevelop Zhongda into a “high-tech zone” — presumably for software companies and other industries. But these industries are not intimately involved in the physical world — they conduct research and development, and deploy applications online. In short, they do not necessarily benefit from being deeply nestled in Guangzhou’s urban centre. Consider that American tech giants like Google, Facebook, and Apple do not have their headquarters downtown. They build massive campuses (which are really like the modern American version of an industrial park) outside of but near to major cities — in other words, in places like Qingyuan. Why doesn’t the local government use new industrial parks for emerging industries, rather than disrupting established ones?

From what I’ve seen of Zhongda market, there is a clear benefit to being in the heart of a city. Migrant workers are close to the train station and their kinship networks spread throughout Guangzhou, factory-owners from other cities can quickly swoop in and out to inspect their workshops, and clients like Shein can easily stop by to check on an order. In short, it is easy for labourers to come and go, as well as for businesses to quickly negotiate low-volume orders. And even though Zhongda is full of old buildings and difficult living conditions, it is a far more vibrant place to live than in an industrial park dormitory.

One day after spending time in Zhongda, I went to a K11 mall in downtown Guangzhou. While walking among the largely empty shops, I found a Vertu store. Vertu is a phone brand that sells excessively expensive mobile devices that are not useful. Many are not even smartphones; one piece that looks like an old Nokia from the early 2000s was selling for Rmb300,000. I thought about how, in the Zhongda market, I paid a man in a workshop Rmb30 to repair a pair of trousers and adjust the sleeves on a shirt (and I was being overcharged — normally they earn about Rmb3 to make one new item of clothing). This one phone likely costs more than he makes from three years of hard work. I thought about where the silly phone was built (likely another factory somewhere in Guangdong), and how much the people who built it were paid. I don’t know a system that works better than capitalism, but in that moment I certainly understood why the government wants to make one. I just don’t think moving Zhongda out of Guangzhou is the best way to achieve that goal.

Zhongda residents relaxing in a workshop during some downtime: